Diving the Cape Peninsula and False Bay

Diving the Cape Peninsula and False Bay

This regional dive guide is intended to provide the already qualified scuba diver with information which will help to plan dives in the waters of the Cape Peninsula and False Bay, whether as a local resident or a visitor. Information is provided without prejudice, and is not guaranteed accurate or complete. Use it at your own risk. Expand or correct it when you can.

The region described is within a day trip by road from any part of greater Cape Town, in the Western Cape province of South Africa, is mostly in coastal and inshore waters bordering the greater Cape Town area, and includes over 300 named dive sites for which positions are recorded, which is a lot for any single destination.

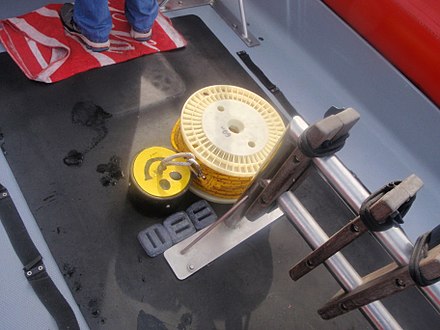

Detailed information on individual dive sites is provided in the sub-articles linked from the list of dive sites of the Cape Peninsula and False Bay. The information in the site descriptions ranges from superficial to highly detailed, depending on what is known about the site, and there may be a map. The bathymetric charts by SURGMAP are updated as and when new survey data is collected, and are mapped by swimming the contours towing a GPS buoy. They are reasonably accurate – within a couple of metres usually – and reliable for what is shown, but seldom complete. It is quite possible that some tall pinnacles have been missed. There is no guarantee that you will not discover one by hitting it with your boat. If you do, please let us know.

In some instances a dive site sub-article will include several sites which are in close proximity, as much of the information will be common to them all. In other cases, usually involving wreck sites, two adjacent sites will each have its own sub-article, but if two or more wrecks lie in the same position, or with substantial overlap, they will be described in the same sub-article.

Understand

General topography

The City of Cape Town was founded at the northern end of the Cape Peninsula, a narrow mountainous strip of land at the most 11 km wide and just over 50 km long. The northern border is the coast of Table Bay, a large open bay with a single island, Robben Island, in its mouth. The city has expanded and as of 2022 extends over the entire Cape Peninsula, and the whole way across the north shore and about halfway down the east shore of False Bay.

A ragged coastline marks the western border along the Atlantic ocean. A number of small bays are found along the coast with a single large one, Hout Bay, about half way along. Further south the peninsula narrows until it comes to an end at Cape Point. A range of mountains with Table Mountain at 1,085 m at the northern end forms the backbone of the peninsula. The highest point of the southern peninsula is Swartkop, at 678 m, near Simon’s Town. The peninsula has fairly steep slopes along most of the coast, with very narrow areas of relatively flat land except for the west side of the southern tip.

The steep eastern side is bordered by False Bay, and this stretch of coastline includes the smaller Smitswinkel Bay, Simon’s Bay and Fish Hoek Bay, where a strip of low ground extends between the coasts on both sides. At Muizenberg the coastline becomes relatively low and sandy and curves east across the southern boundary of the Cape Flats to Gordon’s Bay to form the northern boundary of False Bay. From Gordon's Bay the coastline swings roughly south, and zig-zags its way along the foot of the Hottentot’s Holland mountain range to Cape Hangklip which is at nearly the same latitude as Cape Point. The highest peak on this side is Kogelberg at 1,269 m.

In plan the bay is approximately square with rather wobbly edges, being roughly the same extent from north to south as east to west (30 km), with the entire southern side open to the ocean. The area of False Bay has been measured at about 1,090 km², and the volume is approximately 45 km³ (average depth about 40 m). The land perimeter has been measured at 116 km, from a 1:50,000 scale map.

The bottom morphology of False Bay is generally smooth and fairly shallow, sloping gently downwards from north to south, so that the depth at the centre of the mouth is about 80 m. The bottom is covered with sediment which ranges from very coarse to very fine, with most of the fine sediment and mud in the centre of the bay. The main exception is a long ridge of sedimentary rock that extends in a southward direction from off the Strand, to approximately level with the mouth of the Steenbras River. The southern tip of this ridge is known as Steenbras Deep.

There is one true island in the bay, Seal Island, a barren and stony outcrop of granite about 200 m long and with an area of about 2 ha. It is about 6 km south of Strandfontein and is less than 10 m above sea level at its highest point. There are also a number of small rocky islets which extend above the high water mark, and other rocks and shoals which approach the surface. Most of these are granite of the Peninsula pluton, but east of Seal Island they are generally sandstone, probably of the Tygerberg formation within the bay, though it is possible that some may be of the Table Mountain series. The largest of these reef areas is Whittle Rock, an underwater hill of granite rising from the sandy bottom at about 40 m to within 5 m of the surface, and about 1 km diameter. There are several smaller, deeper areas of granite reef in the vicinity of Whittle Rock.

Outside the bay, but influencing the wave patterns in it, is Rocky Bank, an extensive reef of Table Mountain sandstone between 20 and 30 m depth on top, and sloping down to deeper than 100 m to the south.

Strictly speaking, False Bay is part of the Atlantic Ocean, which extends as far as Cape Agulhas, but when in Cape Town, Atlantic generally refers to the western seaboard of the Cape Peninsula, and the east side is referred to as False Bay, or the Simon's Town side. This convention will be used throughout this guide.

Local topography

The strongest influence on local topography is the local geology. Unconsolidated deposits of silt, sand or gravel tend to be fairly flat. Shingle and small boulders may slope more steeply, and bedrock and large boulders may be anything from raised slightly above the surrounding unconsolidated bottom, to overhanging cliff faces and tors. The rock type, and for sedimentary strata, the dip and strike, have a major influence on the range of possible reef forms.

The present reef structures developed as landforms during the ice ages, when they were above sea level, and the granite reefs were largely shaped by underground weathering process over even longer periods. The granites are old, and much jointed by tectonic forces, and the edges of the cracks have had a long time to be chemically eroded by ground-water to round off the corners and form deep crevices and gullies, which were later exposed by erosion of the saprolith and further modified by weathering and erosion of the exposed surfaces to the structures known as corestones and tors. Similarly, the exposed sedimentary rock eroded while exposed above ground. When the sea level rose during the glacial melting, these landforms simply flooded, and retain much of their previous form and character. Coastal erosion has since modified reefs in areas exposed to high enough energy wave action, and some movement of sediment occurs due to waves and currents.

Climate

The climate of the South-western Cape is markedly different from the rest of South Africa, which is a summer rainfall region, receiving most of its rainfall during the summer months of December to February. The South-western Cape has a Mediterranean type climate, with most of its rainfall during the winter months from June to September.

The climate of the South-western Cape is markedly different from the rest of South Africa, which is a summer rainfall region, receiving most of its rainfall during the summer months of December to February. The South-western Cape has a Mediterranean type climate, with most of its rainfall during the winter months from June to September.

During the summer the dominant factor determining the weather in the region is a high pressure zone, known as the Atlantic High, located over the South Atlantic Ocean to the west of the Cape coast. Winds circulating in an anticlockwise direction from such a system reach the Cape from the south-east, producing periods of up to several days of high winds and clear skies. These south easterly winds are locally known as the Cape Doctor. They keep the region relatively cool and help to blow polluted air from the industrial areas and Cape Flats out to sea. Because of its south facing aspect False Bay is exposed to these winds, particularly on the west side, while Table Bay and the west coast of the peninsula, and the east side of False Bay from Gordon's Bay to Cape Hangklip, experience an offshore wind. This wind pattern is locally influenced by the topography to the extent that gale force winds may be blowing in Gordon's Bay , while about 10 km away parts of Somerset West may have a sweltering and windless day.

Winter in the South-western Cape is characterised by a northward shift in the disturbances in the circumpolar westerly winds, resulting in a series of eastward moving frontal depressions extending far enough north to pass over the Western Cape. These bring cool cloudy weather, wind, and rain from the north-west, followed by a drop in temperature and a shift to south-westerly wind as the front passes. The south westerly winds over the South Atlantic produce the prevailing south-westerly swell typical of the winter months, which beat on the exposed Atlantic coastline and the east side of False Bay. The mountains of the Cape Peninsula provide protection within the west side of False Bay from this wind and from the south westerly waves – a fact which influenced Governor Simon van der Stel in his choice of Simon’s Bay as a winter anchorage for the Dutch East India Company’s ships for Cape Town. The north-westerly winter storms have wrecked many ships anchored in Table Bay over the centuries. Even today, in spite of technical advances and improved weather forecasting this still happens, though less frequently than in the past, and these days the salvage operations are more often successful.

Weather

The general trend is for the weather to come in from the west and move eastwards with the frontal systems, but there can also be more local weather phenomena such as thunderstorms (rare) and 'berg' winds, which are warm winds coming down over the mountains from inland. There can be considerable variation in weather conditions between different sites in the area covered by this guide on any day, though the general tendency may be similar. For example rain may fall on the Cape Peninsula in the morning, and by afternoon these conditions may have moved over to the east side of False Bay and the peninsula may be clearing with a significant wind directional shift from north-westerly to south-westerly. Local variation in wind strength may be extreme, and sometimes hard to believe, as there may be a dead calm in one place and a howling wind a few kilometres away. There are places known for exposure to both south easterly and north westerly winds, and some which are sheltered from one or the other, while the south-westerlies blow most places, but not usually to quite the same extremes. What this amounts to in practice, is that the weather conditions where you are at a particular time may differ significantly from those at a dive site a bit later in the day.

A berg wind is caused by a high altitude inland high pressure, usually in winter, on the cold, dry central plateau areas above the great escarpment, coupled with lower pressures at the coast. The wind flows down the escarpment and is heated by compression. The temperature rise can be considerable and over a short period. This hot, dry wind is offshore and does not greatly affect diving conditions, but it is usually followed by cool onshore winds with low cloud, fog and drizzle, and is often associated with the approach of a cold front from the west in winter, which may bring strong westerly winds and substantial frontal rain.

Waves and swell

The waves reaching the shores of False Bay and the Cape Peninsula can be considered as a combination of local wind waves and swell from distant sources. The swell is produced by weather systems generally south of the continent, sometimes considerably distant, the most important of which are the frontal systems in the South Atlantic, which generate wind waves which then disperse away from their source and separate over time into zones of varying period. The long period waves are faster and have more energy, and move ahead of the shorter period components, so they tend to reach the coast first. This is known to surfers as a pulse, and is generally followed by gradually shortening period swell of less power.

Local winds will also produce waves which will combine their effects with the swell. Offshore winds as a general rule will flatten the sea as the fetch (distance that the wind has blown over the water) is usually too small to develop waves of great height or length. Onshore winds on the other hand, if strong enough will produce a short and nasty chop which can make entry and exit uncomfortable, and surface swims or boat rides unpleasantly bumpy and wet.

The combination of swell and wind waves must be considered when planning a dive. This requires knowledge of these conditions, which are forecast with variable accuracy by a number of organisations, in some cases for seven or more days ahead. Accuracy is generally inversely proportional to the interval of the forecast. It is usually quite reliable looking two or three days ahead, but can be a little shaky over more than a week. Weather is like that.

Upwellings

South-easterly winds which blow offshore and along the coast on the west side of the Cape Peninsula and the east side of False Bay cause a movement of surface water offshore to the west of the coast due to Ekman transport. This movement of water away from the coast is compensated by the upwelling of deeper water.

These upwellings are of considerable interest to the diver, as the upwelled water on the west coast is cold and relatively clear. However, as the upwelled water has a high nutrient content, the upwellings are often forerunners of a plankton bloom known as a "red tide", which will drastically reduce visibility, often in a matter of hours in strong sunshine. Water temperature tends to drop to below 12°C during a west coast upwelling, and can reach a chilly 7°C on occasion.

On the east side of False Bay the upwellings often cause poor visibility as they can disturb the very fine and low density sediment which is common on that side of the bay, particularly in the shallower part near Gordon's Bay. The water is also relatively cold, but not usually as cold as on the west side of the peninsula and temperatures may drop from around 19°C to 12°C over a day or two.

Tides

The local tides are lunar dominated, semi-diurnal, and relatively weak, and there are no strong tidal currents on the Atlantic coast or in False Bay. The resulting tidal flows are of little consequence to the diver, the main effect being slight changes in the depth at the dive site and variations on the obstacle presented by kelp fronds near the surface, which can affect the effort required to get through the kelp at the surface. In this regard it is generally easier at high tide.

Boat launches at some slipways can be difficult at low tide, which can occasionally affect boat dive schedules, and spring low is at roughly the time of first launch (roughly 09:00 to 09:30).

Maximum tidal range at Cape Town is approximately 1.86 m (spring tides), and at Simon’s Town 1.91 m, with minimum ranges at both places of about 0.26 m (neap tides).

Water temperature

Average summer surface temperature of the Atlantic off the Cape Peninsula is in the range 10° to 13°C. The bottom temperature may be a few degrees colder. Minimum temperature is about 8°C, though claims have been made for as low as 6°, and maximum about 17°C.

Average winter surface temperature of the Atlantic off the Cape Peninsula is in the range 13° to 15°C. The bottom temperature inshore is much the same.

Average winter surface temperature of False Bay is approximately 15°C, and the bottom temperature much the same or a bit lower. Average summer surface temperature of False Bay is said to be approximately 19°C. The bottom temperature is generally 1° to 3°C lower than it is in winter, but 10° to 12°C is not unknown. A thermocline will usually develop in False Bay in late summer. This will usually become more distinct and get deeper in autumn as the surface water warms up.

Currents

Currents are not usually considered an issue at most dive sites in this region. A shallow surface current may be produced by strong winds, over a short period, which can be an inconvenience if it sets offshore. The depth of the current depends on how long the wind has been blowing, and when a sudden wind picks up while one is diving, the current is shallow and a diver may return to shore at 3 to 6 m depth below most of the current. Tidal currents are negligible, and are only experienced at a few isolated dive sites, such as Windmill Beach, during spring tides when there is some swell running. Bear in mind that a surface current driven by wind will flow to the left of the wind direction due to Coriolis effects, and the angle will increase and strength will decrease with the depth.

Two places which may experience significant currents are at the mouth of False Bay, at Rocky Bank and Bellows Rock, where eddies from the Agulhas current frequently produce a light- to medium-strength current, which may be strong enough to inconvenience divers in the shallows around Bellows Rock. Occasionally currents of up to about a knot have been experienced at offshore dive sites in False Bay south of Simon's Town, and on the Atlantic seaboard near Duiker Point and Robben Island. These currents are usually considerably weaker at the bottom, and do not usually present much difficulty to divers, though they make the use of a DSMB for surfacing more important, as one can drift quite a long way even on a normal ascent with a safety stop. These surface currents can be more of an inconvenience at the start of the dive, as they will carry you past the shotline if you are not prompt about descending, which should be done as soon as the line is in view. Also, depending on the slack in the shotline, the buoy will be downwind and downcurrent of the mark by several metres. A competent skipper will make some allowance and drop the divers in upstream of the buoy. Competent divers will descend as soon as they can see the shotline, to avoid drifting past the mark. In many cases it will not matter much to descend a bit off the mark, but for wrecks overshooting the mark can mean missing the wreck altogether.

Predicting the weather and sea conditions

Predicting diving conditions in this region is fairly complex. There are websites such as Buoyweather, Surf-Reports and Windguru which provide reasonably reliable forecasts for wind and swell. This combined with information on recent conditions of water temperature and visibility will allow a fairly reliable prediction of conditions a few days in advance. The local Wavescape website and surf report is also a valuable reference with a distinctive South African ambience, though like the others, it is primarily intended for surfers, and divers must interpolate a bit.

Visibility can clear up quite quickly (overnight) on the Atlantic coast due to currents and relatively coarse sediments. On the west side of False Bay it is a little slower, and it can take several days, even weeks, on the east side of the bay, where the sediments are fine and light.

Satellite sea surface temperature and chlorophyll data are also available off the internet, and may help predict surface conditions, but how much they predict bottom conditions is not known.

Until you have developed a feel for this procedure, it is useful to get second opinions from people or organisations with experience.

Some of the local dive charter operators have better reputations for weather prediction than others, and there are some who will almost always claim that conditions are or were good. The Blue Flash weekly newsletter is as good as any other and better than many. This will refer to the preferred areas off the Cape Peninsula, including the west side of False Bay. For information on the east side of False Bay you can try phoning Indigo Divers.

The marine ecology

The bioregions

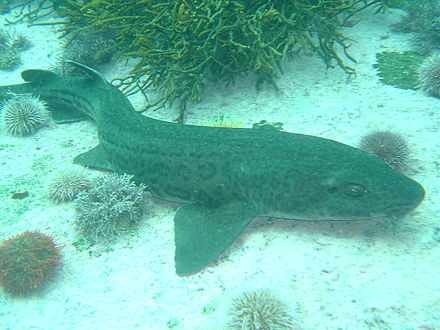

Cape Point at the tip of the Cape Peninsula is considered the boundary between two of the five inshore marine bioregions of South Africa. To the west of Cape Point is the cool to cold temperate South-western Cape inshore bioregion, and to the east is the warmer temperate Agulhas inshore bioregion. The Cape Point break is considered to be a relatively distinct change in the bioregions and this can be clearly seen from the difference in marine life between the Atlantic seaboard of the peninsula and False Bay.

The habitats

Four major habitats exist in the sea in this region, distinguished by the nature of the substrate. The substrate, or base material, is important in that it provides a base to which an organism can anchor itself, which is vitally important for those organisms which need to stay in one particular kind of place. Rocky shores and reefs provide a firm fixed substrate for the attachment of plants and animals. Some of these may have Kelp forests, which reduce the effect of waves and provide food and shelter for an extended range of organisms. Sandy beaches and bottoms are a relatively unstable substrate and cannot anchor kelp or many of the other benthic organisms. Finally there is open water, above the substrate and clear of the kelp forest, where the organisms must drift or swim. Mixed habitats are also frequently found, which are a combination of those mentioned above. The habitats are described in more detail in the following sections.

Rocky shores and reefs

The great majority of popular dive sites in the local waters are on rocky reefs or mixed rocky and sandy bottoms, with a significant number of wrecks, which are equivalent to rocky reefs for classification of habitat, as in general, marine organisms are not particular about the material of the substrate if the texture and strength is suitable and it is not toxic. For many marine organisms the substrate is another type of marine organism, and it is common for several layers to co-exist. Examples of this are red bait pods, which are usually encrusted with sponges, ascidians, bryozoans, anemones, and gastropods, and abalone, which are usually covered by similar seaweeds to those found on the surrounding rocks, usually with a variety of other organisms living on the seaweeds.

The type of rock of the reef is of some importance, as it influences the range of possibilities for the local topography, which in turn influences the range of habitats provided, and therefore the diversity of inhabitants.

Granite reefs generally have a relatively smooth surface in the centimetre to decimetre scale, but are often high profile in the metre scale, so they provide macro-variations in habitat from relatively horizontal upper surface, near vertical sides, to overhangs, holes and tunnels, on a similar scale to the boulders and outcrops themselves. There are relatively few small crevices compared to the overall surface area.

Sandstone and other sedimentary rocks erode and weather very differently, and depending on the direction of dip and strike, and steepness of the dip, may produce reefs which are relatively flat to very high profile and full of small crevices. These features may be at varying angles to the shoreline and wave fronts. There are far fewer small caverns and swimthroughs in sandstone reefs, but often many deep but low near-horizontal crevices. In some areas the reef is predominantly wave-rounded medium to small boulders. In this case the type of rock is of little importance.

The coastline in this region was considerably lower during the most recent ice-ages, and the detail topography of the dive sites was largely formed during the period of exposure above sea level. As a result, the dive sites are mostly very similar in character to the nearest landscape above sea level.

There are notable exceptions where the rock above and below the water is of a different type. These are mostly in False Bay south of Smitswinkel Bay, where there is a sandstone shore with granite reefs.

Kelp forests

Kelp forests are a variation of rocky reefs, as the kelp requires a fairly strong and stable substrate which can withstand the loads of repeated waves dragging on the kelp plants. The Sea bamboo Ecklonia maxima grows in water which is shallow enough to allow it to reach to the surface with its gas-filled stipes, so that the fronds form a dense layer just below the surface. The shorter Split-fan kelp Laminaria pallida grows mostly on deeper reefs, where there is not so much competition from the sea bamboo. Both these kelp species provide food and shelter for a variety of other organisms, particularly the Sea bamboo, which is a base for a wide range of epiphytes, which in turn provide food and shelter for more organisms.

The Bladder kelp Macrocysta angustifolia can also be found at a few sites, mostly near Robben Island. This is one of the few places in the world where three genera of kelp may be found at the same place.

Sandy beaches and bottoms (including shelly, pebble and gravel bottoms)

Sandy bottoms at first glance appear to be fairly barren areas, as they lack the stability to support many of the spectacular reef based species, and the variety of large organisms is relatively low. The sand is continually being moved around by wave action, to a greater or lesser degree depending on weather conditions and exposure of the area. This means that sessile organisms must be specifically adapted to areas of relatively loose substrate to thrive in them, and the variety of species found on a sandy or gravel bottom will depend on all these factors.

For these reasons sandy and gravel bottoms are not usually popular with novices and visitors, who are usually attracted to the more spectacular sites, but to the diver who is interested in the full variety of the marine environment they can provide a refreshing and fascinating variation, as there are a lot of organisms which will only be found on these bottom types. Mostly they can be found adjacent to reef areas, but there are a few sites which are predominantly sandy.

Sandy bottoms have one important compensation for their instability, animals can burrow into the sand and move up and down within its layers, which can provide feeding opportunities and protection from predation. Other species can dig themselves holes in which to shelter, or may feed by filtering water drawn through the tunnel, or by extending body parts adapted to this function into the water above the sand.

Red tides

On the west coast of the peninsula and to a lesser extent the east side of False Bay, the south easterly winds can cause upwelling of deep, cold, nutrient rich waters. This generally happens in summer when these winds are strongest, and this in combination with the intense summer sunlight provides conditions conducive to rapid growth of phytoplankton. If the upwelling is then followed by a period of light wind or onshore winds, some species of phytoplankton can bloom so densely that they colour the water, most noticeably a reddish or brownish colour, which is known as a red tide.

Depending on the species involved, these red tides may cause mass mortalities to marine animals for various reasons. In some cases the organisms may consume all the available nutrients and then die, leaving decaying remains which deplete the water of oxygen, asphyxiating the animal life, while others may simply become so dense that they clog the gills of marine animals, with similar effect. A third group are inherently toxic, and these may be particularly problematic as some filter feeding species are immune to the toxins but accumulate them in their tissues and will then be toxic to humans who may eat them.

Red tides also have the more direct effect on diving conditions of reducing visibility. The reduction in visibility can range from a mild effect in the surface layers, to seriously reduced visibility to considerable depth.

Red tides may be small and localised and usually last for a few days, but in extreme cases have been known to extend from Doringbaai to Cape Agulhas, several hundred kilometres to both sides of Cape Town, and take weeks to disperse (March 2005).

Equipment

Standard equipment

Most of the dive sites in this region are relatively shallow and can be done on air with ordinary recreational diving equipment, which would include:

- A full wet-suit of at least 5 mm thickness, hood, boots and gloves.

- A cylinder with harness, regulator and submersible pressure gauge. Most rental cylinders are 10 litre, 12 litre dumpy or 15 litre steel 232 bar, usually with DIN outlet valves with removable plug adaptors to take yoke connection regulators. Check before booking a cylinder if you will be using your own regulator.

- A buoyancy compensator device (BCD).

- Mask and snorkel.

- Fins.

- A ditchable weight system correctly calibrated for the rest of the equipment.

- A dive computer or a depth gauge and timer with decompression tables and dive plan.

To this you can add:

- Any further equipment you or your certifying agency may consider obligatory, such as a secondary regulator, low pressure BCD inflator, knife, etc.

- Any equipment you carry or use as a matter of personal preference, such as camera, signalling device, wrist slate, dry suit, reel and surface marker buoy, alternative gas supply, compass, etc.

Recommendations

- If your fins have full foot pockets (closed heel), and your wet suit boots have soft soles, it may be necessary to wear shoes to get to the entry point on shore dives. Open heel fins and hard soled boots are recommended for most shore dives in this region because the ground tends to be rough and shoes may not still be where you left them when you return from the dive.

- A standard surface marker buoy is not recommended where there is heavy kelp growth, as it will snag frequently and provide endless annoyance. A deployable or “delayed” surface marker is better at such sites and is always a good thing to carry on a boat dive.

- Leaving out any of the above items is at your own risk. There are divers who will not wear hoods, or gloves, or boots, or feel that a snorkel or BC is not necessary, or that they can dive in a 3 mm suit. Try this on an easy dive first, where you can get out quickly. It may work for you – there are divers who manage in each of these cases, but you have been warned.

Additional equipment

For each dive site there may be additional or alternative equipment required or recommended, which may improve the dive experience or improve safety at that site. The most commonly recommended items are:

- Compass

- Dry suit

- Light

- Nitrox

- Reel with DSMB

Use of a compass is recommended wherever it may be desirable to swim back to shore below the surface to avoid wind or boat traffic, or to keep below the kelp fronds. It is required for the compass navigation routes.

A dry suit is recommended for most dives on the Atlantic seaboard, or in general if the dive is deeper than about 20 m and the water is colder than 13°C. An appropriate undergarment is required for the dry suit, as this is what provides the insulation. With a suitable combination it is possible to enjoy an hour's dive in comfort at a water temperature of 8°C, when most of the divers in 7-mm wetsuits are cold after 30 minutes. If your face and head are particularly sensitive to cold, a full-face mask will keep your face warm.

Recommendations for a light are for daytime dives, as lights are considered standard equipment on night dives. Backup lights should be carried on night dives from a boat. Underwater flashers may not be well received by the other divers as they are extremely annoying. If you feel you must use one, warn the others and stay away from those divers who do not wish to have a light continually flashing in their peripheral vision and distracting them. A strobe which may be switched on in an emergency is another matter entirely, and is accepted as a valuable safety aid.

The equipment recommendations are for divers who are competent to use those items, and if you are not, you should consider whether your competence is sufficient to dive the site without this equipment.

No recommendations are made regarding equipment for wreck penetration dives and deep dives. If you do not know exactly what equipment is required and have it with you, or are not competent in its use, you should not do the penetration. Depth, wrecks and caves are nature’s tools for culling reckless divers.

Recommendations for gas mixtures are generic. You must choose the appropriate mixture based on your qualifications, competence and the dive plan. Nitrox mixtures are generally recommended to increase dive time with or without obligatory decompression stops, and Trimix to reduce narcotic effects. Nitrox is available from many of the dive shops, and charter operators will usually provide cylinders filled with the blend of your choice if given sufficient notice. Trimix is more difficult to arrange, as not many filling stations keep helium in stock, so it may require a bit of shopping around, and it will be expensive.

Decompression dives should generally only be planned by divers who are familiar with the site, and are competent and properly equipped for the planned dive. Recommendations in this regard are outside the scope of this article, and it will be necessary to discuss any planned decompression dives well in advance with the dive operator, as only a few of them are competent and willing to support planned decompression dives, and those will usually require strong evidence of your competence to do the dive, and advance notice of your dive plan.

Exotic equipment

Diving equipment other than open circuit back mounted scuba with half mask and mouth-grip demand valve is considered to be exotic for this section.

This would include surface supplied breathing apparatus and full face masks, used as standard equipment by commercial divers, and rebreathers, seldom used by commercial divers, but frequently used by military divers and gaining popularity with technical recreational divers.

Diving equipment other than open circuit back mounted scuba with half mask and mouth-grip demand valve is considered to be exotic for this section.

This would include surface supplied breathing apparatus and full face masks, used as standard equipment by commercial divers, and rebreathers, seldom used by commercial divers, but frequently used by military divers and gaining popularity with technical recreational divers.

Also considered as exotic equipment is side-mount scuba and diver propulsion vehicles (scooters), as they are not used by many recreational divers.

Generally speaking, any use of surface supplied diving equipment will require special preparation and logistics, which are not available from the listed service providers, but are perfectly legal for use and technical support is available from the suppliers to the commercial diving industry in Cape Town.

Rebreathers are relatively uncommon, but are used by a few local aficionados, and sorb is available over the counter at a few suppliers. There is even one charter boat which regularly runs dives for mainly rebreather divers. Expect to be checked out for skills and certification before being allowed to join these dives, so it would be advisable to make prior arrangements. Technical support is available for a limited range and parts will usually only be available from overseas agencies. Most of the local dive sites do not really justify the expense and relative risk of rebreathers, and they are mostly used by divers who also use them in other places where they are more of an advantage, and by those who just enjoy the technology. They are not available for rental, except in some cases as part of a training package.

Full-face masks will not be a problem, provided you can show your ability to provide buddy support if diving with a partner (some charters will insist that you dive with a buddy). Technical support and parts are available from local agencies for most of the more popular models used for commercial and technical diving, but you may have to wait some time if parts are not in stock. The use of a full-face mask can be a particular advantage when the water is cold, and if you have one and prefer to use it, by all means bring it to Cape Town.

Side mount scuba is relatively uncommon in Cape Town, but there should be no problems if you choose to use it. Do not expect boat crews to know how to help you kit up, but they will probably respond well to explanations. There is a growing number of local side-mount aficionados, including several instructors for side-mount.

Diver propulsion vehicles (scooters) are rare but not unknown. Check with the charter boat whether will be space on board for your unit, and don't expect to find one for rental.

Decompression and bailout sets are not considered exotic, but are not easily available for rental. Bring your own, or ask around. Some of the service providers carry a small range of cylinders suitable for sling mount, but may not have the gas mixture you want in stock. Almost all the local divers that carry decompression or bailout cylinders routinely have their own equipment.

Permits and conditions of use

A permit is required for diving in a marine protected area, and most of the dive sites of the Cape Peninsula are in the Table Mountain National Park Marine Protected Area (TMNPMPA) or the Robben Island MPA (RIMPA). Annual permits are available from some branches of the Post Office, and temporary permits are usually available from dive boat operators and dive shops. These authorise recreational non-extractive scuba diving in the MPAs and their zones where scuba diving is allowed during the day. In the TMNPMPA this is all zones. In the RIMPA all zones except the inshore exclusion zone, within a nautical mile of the water's edge.

Night dives require that SANParks be notified (021-786 5656), and are allowed up to 11pm. No diving may be done between 11pm and 4am.

Dive sites

The dive sites of the Cape Peninsula and False Bay can be grouped in a few sub-regions, each with common features and their own particular character regarding geographic location and weather conditions which affect them.

The dive sites described in the site articles include some which are well known favourites and have been dived frequently and by many divers for decades, and also newly described sites, which may only have been dived a few times, and by a few divers. There are also sites which have been known for years, but seldom dived due to their relative inaccessibility, and a few which are basically not particularly interesting, but have been included in the interests of completeness, as the information is available, and occasionally people want to know what they are like, or may need to dive there for some reason. With a few exceptions, the information provided is based on personal observation at the sites by Wikivoyagers. All photos of marine life and features of interest were taken at the listed site.

Geographical information is provided in as much detail as is available. Sites are geolinked, which allows them to be identified on various internet map systems. Positional accuracy is usually good. The maps provided should be usable, to scale, and accurate, but are not guaranteed either to be correct in all details or complete. Clicking on the thumbnail will open a link to a higher resolution image.

Atlantic coast of the Cape Peninsula

Main article: Dive sites of the Cape Peninsula west coast

Introduction and some tips on diving the Atlantic coast.

This coastline from Table Bay to Cape Point is exposed to the south westerly swells generated by the cold fronts of the Southern Ocean. The continental shelf is narrow in this part of the coast and swells are not greatly influenced by the narrow band of shallow water, so they retain most of their deep-water energy. These swells pound this coast most of the winter, and to a lesser extent in summer, so diving in this region is mostly a summer activity, and the frontal weather patterns far to the south are more important than local weather for swell prediction.

North westerly winds are a feature of the approach of a cold front, and in winter they can be very strong for a few days before swinging to southwesterly as the front passes. These north westerly winter storms were responsible for many shipwrecks in Table Bay and other parts of the west coast, and the associated wind waves can be severe. However the fetch is short and these onshore wind waves do not last long after the storm. They do mess up the visibility though, and this effect lasts for some time after the waves have dissipated.

The south easterly winds are longshore to offshore in this area and tend to knock the swell down a bit. They also cause an offshore displacement of the surface water, which results in deeper water rising to take its place. This upwelling brings colder, initially cleaner water to the inshore areas, and can produce conditions of 20 m+ visibility and temperatures down to 8°C, though more usually 10° to 12°C. The diving is wonderful if you are sufficiently insulated. Out of the water, however, it is commonly fine and hot, with blazing sunshine high ultraviolet levels and air temperatures in the high 20 and 30° Celsius. This means you will be overheating until you get in the water, hence the comment that summer diving in Cape Town is one easy step from _hyper_thermia to _hypo_thermia.

There is no escaping the need for a well-fitting, thick (preferably 7 mm), wet suit or a dry suit with an adequate undergarment for these conditions if you intend to stay for more than a few minutes. Carrying a bottle of water with your equipment to wet the outside of your suit before or after putting it on will help keep the temperature down due to evaporative cooling, specially on a windy day. Overheating after leaving the water is seldom a problem. The alternative option of kitting up at the water’s edge requires a shore party to look after your clothes, etc., while you dive, so it has become less common. Do not leave equipment unattended if you wish to see it again.

An upwelling is frequently followed by a plankton bloom, often called a red tide. This will reduce visibility considerably, particularly near the surface. Often the water will be much clearer below the surface layer, though the light levels may be a bit dim and the colour relatively green, or even brownish. The phytoplankton will bloom while the sun shines, so it is much more developed in summer.

The south-easter is an offshore wind at some sites, and besides its influence on temperature and visibility, it also affects the swim back to shore after the dive. The south-easter can appear seemingly out of nowhere on a previously cloudless and windless day, and build up to near gale force in the time you are underwater on a dive, though it is usually predictable, so take note of weather forecasts, and in any case, allow sufficient reserve air to swim back a few metres below the surface. A compass is extremely useful if you do this as it allows you to swim shallower, which is good for air consumption, decompression and warmth. A depth of 3 to 5 m is recommended for a long swim home. The strong south-easter in these cases produces a short, steep wind chop with white-caps which does not penetrate to any significant depth, but the constant slapping of waves and the spray in the air can make snorkelling unpleasant and difficult. There may also be a shallow offshore wind drift (surface current), but this takes some time to develop and gets rapidly weaker with depth and is not usually a problem below about a metre depth inshore. Further offshore the wind induced current can take you several hundred metres during a decompression stop, at a rate of about 0.5 to 1 kph.

When boat diving a deployable surface marker buoy (DSMB) is useful to both facilitate controlled ascent and accurate decompression or safety stop depth, and as a signal to the boat that you are on your way up. In strong wind conditions it will also improve your visibility on the surface, specially if your equipment is all black, so it is worth carrying even if only as a signalling device. Bright yellow has been shown to be best for all round visibility at sea, but orange and red are fairly good too.

False Bay coast of the Cape Peninsula

Main article: Dive sites of the Cape Peninsula east coast

Introduction and some tips on diving the False Bay coast of the Cape Peninsula (Simon's Town side)

Unlike the rest of the region, the west side of False Bay is sheltered from the winter westerlies, but in return it takes the South-Easter head on. As a result of this the region is usually dived in winter, when the South-Easter seldom blows for long or with great force.

The winter frontal storms over the Southern Ocean produce swells which are slowed by the continental shelf and refracted and diffused round the Cape Peninsula, so that they propagate mostly parallel to the coastline, and have lost much of their energy by the time they curve in towards the shore. The irregular form of the coast here also protects some areas more than others. Generally speaking, those parts of the coast which run in a more north west to south east direction are better protected from the south west swell than the north to south parts, so the choice of dive site is dependent on the recent weather patterns.

During the summer months when the South-Easter blows more frequently, for longer, and generally harder, this area is not as often diveable, and the visibility is generally poorer than in winter even when conditions are otherwise suitable.

The water temperature during the winter months in this area is generally warmer than the Atlantic coast in summer, which is some compensation for the shorter daylight hours and often cold and rainy weather.

Water temperature may vary with depth. There is usually a thermocline in summer, and the visibility may change significantly below the thermocline. The surface can be 18 or 19°C with 10 or 11°C at the bottom, but the difference is more likely to be 5°C or less. Conditions at depth are not easily predictable, and may be better or worse than near the surface. There can be a plankton bloom in the surface layers and a sudden improvement in visibility from 3 m or less to over 10 m in the cold bottom water. The depth of the thermocline is also not very predictable, but has been known to be between 12 and 20 m in late summer.

In winter the water may be the same temperature from top to bottom, and as there is less sunlight to power the phytoplankton blooms, the visibility and natural illumination can be better even though there is less light at the surface.

Between the cold and rainy fronts there are frequently days of little or no wind, and mild to warm sunshine, when the water is flat and clear and the diving is wonderful, and the large number of sites make it difficult to decide where to go as there is so much choice. It’s a tough life here at the end of Africa, but somebody has to do it.

Water temperature during winter is usually between 13°C and 17°C, though it has been known to drop as low as 11°C, so a good suit is also needed here. In summer the temperature may rise above 20°C, but is more likely to be around 17°C to 19°C.

Most of the shore dives are relatively shallow, in the order of 8 m to 15 m maximum depth, though it is possible to do a 30 m shore dive if you don’t mind a 700 m swim to get there. The shallow waters make a dry suit less advantageous, but getting out of a wet suit in the wind and rain at night push the dry suit up again as a desirable option. It is nice to have the choice, and many local divers switch between wet and dry suits depending on the dive planned.

False Bay offshore and approaches

Main article: Dive sites of False Bay offshore and approaches

Introduction and some tips on diving the Central False Bay sites.

All the sites in this area are fairly far offshore, and can only be done as boat dives. They are also relatively deep and because of the long boat trip and exposed positions, generally only dived when conditions are expected to be good.

This area is exposed to the same south westerly swells as the Atlantic coast, but they must travel over a much wider continental shelf, much of which is less than 100 m deep, so there is a significant dissipation of wave energy before it reaches the shoreline.

During summer the strong south easterly winds have sufficient fetch to produce sea states which are unpleasant and though the wave action may not produce a great deal of surge at the bottom, the surface conditions may be unsuitable for diving, and in winter the north-wester can have a similar effect.

As the area is affected by the winds and wave systems of both winter and summer, there is less seasonal correlation to suitable conditions, and it is simply dived when conditions are good, which is not very often, but may be more often than previously thought, and at some reefs the visibility may be better than inshore.

It is quite common for the surface visibility offshore to be poor, with better visibility at depth, but the reverse effect can also occur. These effects are often associated with a thermocline, which is associated with midsummer to autumn.

Water temperature can differ with depth in summer from 20°C on the surface to 9°C at the bottom at 28 m, sometimes with a distinct thermocline, though usually there is less of a change, and in winter the temperature may be nearly constant at all depths. A dry suit is recommended for any of these dives, but they are also often done in wetsuits.

There is often a surface current associated with wind at the offshore sites, which generally sets to the left of the wind direction.

False Bay east coast

Main article: Dive sites of False Bay east coast

Introduction and some tips on diving the False Bay east coast from Gordon’s Bay to Hangklip.

This coast is exposed to the same south westerly swells as the Atlantic coast, but they must travel over a much wider continental shelf, much of which is less than 100 m deep, so there is a significant dissipation of wave energy before it reaches the shoreline. There are other influences, as some of the swells must pass over the shoal area known as Rocky Bank in the mouth of False Bay, and this tends to refract and focus the wave fronts on certain parts of the shore, depending on the exact direction of the wave fronts. As a result there is a tendency for some parts of the coast to be subjected to a type of “freak wave” which appears to be a combination of focused wave front, superposition sets and the effects of the local coastal topography. There are a number of memorial crosses along the coast to attest to the danger of these waves, though the victims are generally anglers, as divers would not attempt to dive in the conditions that produce these waves.

This area, like the Atlantic coast, is mainly a summer diving area, though there will occasionally be suitable conditions for dive at other times of the year. Even in milder conditions there tend to be more noticeable sets in the swell than on the Atlantic coast, and it is prudent to study the conditions for several minutes when deciding on an entry or exit point, as the cycle can change significantly over that time. Timing is important at most of these sites, and often when returning to the shore it may seem that the conditions have deteriorated dangerously during the dive. If this happens, do not be in a rush to exit, hang back for at least one cycle of sets, and time your exit to coincide with the low energy part of the cycle, when the waves are lowest and the surge least. When you exit in these conditions, do not linger in the surge zone, get out fast, even if it requires crawling up the rocks on hands and knees, and generally avoid narrow tapering gullies, as they concentrate the wave energy.

The local geology has produced a coastline with much fewer sheltered exit points on this side of the bay, adding to the difficulty, but there are a few deep gullies sufficiently angled to the wave fronts to provide good entry and exit points in moderate conditions. The most notable of these is at Percy’s Hole, where an unusual combination of very sudden decrease in depth from about 14 m to about 4 m, a long, narrow gully with a rocky beach at the end, and a side gully near to the mouth which is shallow, wide, parallel to the shoreline, and full of kelp, results in one of the best protected exits on the local coastline. As a contrast, Coral Garden at Rooi-els, which is about 1.7 km away, has a gully that shelves moderately, with a wide mouth and very small side gullies, which are very tricky unless the swell is quite low.

There is no significant current in False Bay, and this results in relatively warmer water than the Atlantic coast, but also there is less removal of dirty water, so the visibility tends to be poorer. The South-Easter is an offshore wind here too, and will cause upwelling in the same way as on the Atlantic coast, but the bottom water is usually not as clean or as cold, and the upwelled water may carry the fine light silt which tends to deposit in this area when conditions are quiet, so the effects are usually less noticeable. These upwellings are more prevalent in the Rooi-els area, which is deeper than Gordon’s Bay.

As in the Atlantic, a plankton bloom frequently follows an upwelling. This will reduce the visibility, particularly near the surface. It is quite common for the surface visibility offshore to be poor, with better visibility at depth, but the reverse effect can also occur, particularly inshore. These effects are often associated with a thermocline.

Surface water temperature on this side of the bay can range from as high as 22°C to as low as 10°C, and the temperature can differ with depth, sometimes with a distinct thermocline.

Fresh water dive sites

See also: Fresh water dive sites of Cape Town

There is only one fresh water site of note in the region which is open to the public. This is the Diving the Cape Peninsula and False Bay/Blue Rock Quarry at the bottom of Sir Lowry’s Pass, near Gordon’s Bay.

Respect

Diving on rocky reefs

As a general rule avoid contact with living organisms. This is obviously impossible in Kelp forests, so it is fortunate that sea bamboo and the split-fan kelp are both fast growing and tough. In fact it is recommended that if you need to steady yourself in a surge, you use the lower part of the kelp stipes as handholds in preference to other organisms if there is no clear substrate to grip. They are generally strongly attached to the substrate as they must withstand a severe battering in storms, so the occasional diver holding on seems a light burden. In some cases small kelp plants may be ripped off in strong surge. You will learn to recognise when this is likely to happen and must then make another plan.

The damage done by divers in our local marine ecology appears to be mostly to slow-growing relatively fragile organisms below the surf zone. The false corals (Bryozoa) appear to be among the more fragile, and all contact with the scrolled, pore-plated and staghorn false corals should be avoided. Hard corals, soft corals, anemones and sea fans should also be treated as very sensitive. Sponges are probably less sensitive to being touched, but are not generally very strong and can tear fairly easily, and are unsuitable for holding on.

Red bait (the very common and prolific large sea squirt Pyura stolonifera) seems to be tough and resilient, and can be used as handholds, as it seems to take no noticeable harm, This does not apply to all ascidians, most are much more delicate. Red bait is also frequently the substrate for other, more delicate organisms, in which case, treat with the care appropriate to the more delicate species.

Kicking the reef and stirring up the sand bottom with your fins is considered bad form and the mark of an unskilled diver. Avoid this by maintaining neutral buoyancy and being aware of your position relative to your surroundings, keep leg and arm movements moderate, trim yourself to allow appropriate body orientation, and avoid dangling equipment, which may bang into the reef or get hooked up on things and cause direct or indirect damage. As a general rule, a horizontal orientation with fins raised above the torso is appropriate and allows maneuvering by using the fins without kicking the reef or stirring up a cloud of sand.

Some photographers seem to have developed a nasty habit of shifting things around to suit the desired composition of the picture. This is extremely irresponsible and should not be done, as the handling may be fatal to some organisms. It is also illegal in Marine Protected Areas, though in practice, virtually impossible to enforce.

Collection of marine organisms is illegal without the appropriate permit. If you need the organisms for some legitimate purpose, get the permit. Otherwise leave them undisturbed, and do not unnecessarily disturb other neighbouring organisms if you do collect.

There are concerns regarding the impact of sport diving on the reef ecology. Some of these may be legitimate, and more study is necessary to test whether this is a real problem. The number of dives in the region has increased significantly over the years, but there is no numerical data available. The number of sites has also increased, so the frequency of dives at most sites will not have increased proportionately. Unfortunately the government department previously known as Marine and Coastal Management, now part of the Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, has seen an opportunity to interfere with sporting activity and has made use of surveys on tropical coral reefs to support an effort to take control of sport diving on the temperate reefs around the Cape Peninsula. No surveys of temperate reefs can be produced to justify their claims and it seems unlikely that their interference will benefit either the ecology or the diving industry.

Marine Protected Areas

Most of the dive sites of Cape Town are in the Table Mountain National Park Marine Protected Area or the Robben Island Marine Protected Area.

Most of the dive sites of Cape Town are in the Table Mountain National Park Marine Protected Area or the Robben Island Marine Protected Area.

A permit is required to scuba dive in any MPA. The permits are valid for a year and are available at some branches of the Post Office. Temporary permits, valid for a month, may be available at dive shops or from dive boat operators. The permits are valid for all South African MPAs.

Boundaries of the table Mountain National Park Marine Protected Area are shown in the image, which also shows the Restricted zones, where in theory, no fishing or harvesting activities are allowed. This does not stop the poachers, and if you have political pull it appears that you can get commercial fishing permits for some of the restricted zones.

The Robben Island Marine Protected Area also has a few moderately popular wreck dives, and the Helderberg Marine Protected Area is in False Bay, but no recreational dive sites are known from that area.

Wreck diving around the Cape Peninsula and False Bay

Diving on wrecks in South Africa is a popular activity, and historical wrecks are legally protected against vandalism and unauthorised salvage and extractive archaeology. An interesting, though not particularly logical consequence of the legislation, is that any wreck automatically becomes a historical wreck 60 years after the date of wrecking, with the effect that a pile of rusty rubbish, which anyone can remove at will, can overnight become a valuable and irreplaceable historical artifact and part of the National Heritage. There seems to be a similar effect on divers, who will assiduously scrabble around in a wreck, in the hope of finding an artifact that they wouldn't bend over to pick up if it lay in the street.

Nevertheless, wreck diving has its attractions, and the waters of the Cape Peninsula and False Bay have a large number of wrecks. The reasons for this are firstly that one of the world's major shipping routes passes round Cape Point, and secondly that the weather and sea conditions in this region can be very rough. The anchorage in Table Bay provides little shelter if the wind is from the north west, which is common in winter, and many ships have been driven ashore in and near Table Bay during winter storms when anchors have dragged or cables failed, and the ship was unable to beat off the lee shore. This happens less frequently since ships were motorised, but every few years another ship is blown ashore in Table Bay due to breakdowns or incompetence.

The list of wrecks is long, but the list of wrecks in areas convenient for diving is much shorter, and a significant number of the wrecks that are probably in convenient areas, have not been found. — Recording an exact position as the vessel went down was not often a high priority to the crews, even when it would have been possible. As a result, there is continued exploration and searches made by the wreck diving enthusiasts for wrecks for which approximate positions are known, and there are a few operators who jealously guard their knowledge of wreck locations so that they can have exclusive access.

Many ships sank a significant distance beyond the point at which they were damaged, and many in water either too deep to dive or right up on the shore, where they were subsequently battered to bits by wave action. Others have deteriorated to the point where the average recreational diver would hardly recognise them as the remains of a ship. As a result of these factors, the number of wrecks which are popular dive sites is a small subset of the total number known, and many of these were originally scuttled, either as naval target practice, or as artificial reefs. These wrecks are dived fairly frequently, as conditions allow.

Get help

In case of emergency

National Hyperbarics has closed indefinitely from January 2011. There is no decompression chamber available for recreational diving accidents in the Cape Town area. Until further notice, contact DAN or Metro Rescue.

In cases where there is a need for life support during evacuation, contact one of the paramedic services such as Netcare 911. If the diver is a DAN member, at least try to contact DAN (Diver Alert Network) during the evacuation, as they will make further arrangements. For non-DAN members contact the paramedic service or Metro Rescue direct.

If you need to transport the casualty yourself, go to the Claremont Hospital Emergency Medical Unit first, where the personnel know about diving accidents and can provide life support and appropriate treatment.

It is strongly recommended that someone from the dive group should accompany the casualty in the ambulance, preferably with a cell phone so that they can answer questions about the incident. The casualty's dive computer should be transported with the casualty, and it is helpful if the person accompanying the casualty knows how to extract the dive history from the computer.

-

DAN Southern Africa 24-hour hotline, +27 82 810-6010, +27 10 209-8112.

-

Netcare 911, 082 911 (domestic). Sea rescue, helicopter, ambulance, hyperbaric chamber, poisons and medical emergency advice line.

-

Metro Rescue, 10177 (domestic).

-

Claremont Hospital Emergency Unit, -33.9865°, 10.4666°, +27 21 670-4333.

-

National Sea Rescue Institute, +27 21 449-3500.

-

Mountain Rescue, +27 21 937-1211.

-

Fire, 107 (domestic).

-

S. A. Police Service, 10111 (domestic).

-

In case of difficulties with an emergency call, 1022 (domestic).

Find out

- Southern Underwater Research Group (SURG), info@surg.co.za. For identification of marine life and field guidebooks. Send a photo to SURG and they will try to identify the organism.

- iNaturalist southern Africa. For identification of plants and animals. Upload an observation photo and location to iNaturalist and one of the contributors may identify the organism. You can also share your knowledge by identifying the subject of your own and others' photos.

- Underwater Africa. “The CPR of diving”: Conservation, promotion and representation. Underwater Africa attempts to serve its members by identifying key issues that affect the growth and success of recreational diving. It is the united voice that speaks on behalf of the sport and its operational function is to create focused programs that positively affect both recreational diving and the underwater environment. Specifically, if you have difficulty getting a diving permit from a Post Office on a foreign passport, or for persons under the age of 16, Underwater Africa will try to sort out your problem, as some Post Office staff are not adequately aware of the rules.

- The Maritime Archaeologist at SAHRA, P O Box 4637, Cape Town, +27 21 462-4502, info@sahra.org.za.

Get service

Learn

See Services directory for contact details.

Dive schools:

- Alpha Dive Centre

- Cape Town Dive Centre

- Dive Action

- Dive and Adventure

- Dive Inn Cape Town

- The Dive Tribe

- Indigo Scuba Diving Centre

- Into the Blue

- Just Africa Scuba

- Learn to Dive Today

- Maties Underwater Club

- Ocean Experiences

- Oceanus Scuba

- Orca Industries

- Pisces Divers

- The Scuba School

- Underwater Explorers (Tech only)

Buy

See Services directory for contact details.

Dive shops:

The retail dealers specialising in diving equipment are listed. Other sporting goods stores may also supply a limited range of diving equipment.

- Cape Town Dive Centre

- Dive Action

- Indigo Scuba Diving Centre

- Into the Blue

- Orca Industries

- Pisces Divers

Scuba cylinder fills:

The listed dealers will fill cylinders for the general public. Some other service providers will fill for members only or for their own students or charter customers. See directory for more details.

- Alpha Dive Centre: Air.

- Cape Town Dive Centre: Air, Nitrox

- Dive Action: Air, Oxygen

- Executive Safety Supplies (ESS): Air.

- Orca Industries: Air, Oxygen compatible air, Nitrox (continuous and partial pressure all percentages), Oxygen.

- Indigo Scuba Diving Centre: Air.

- Into the Blue: Air.

- Pisces Divers: Air, Oxygen compatible air, Nitrox (partial pressure all percentages), Oxygen

- Research Diving Unit: Air, Oxygen compatible air, Nitrox (continuous and partial pressure).

- The Scuba School: Air up to 300 bar, Nitrox

Rent

See Services directory for contact details.

Some dive operators will rent you equipment when you dive with them. Check when making a booking. The listed operators rent full scuba equipment. Most charter boats will provide full cylinders on request.

- Cape Town Dive Centre

- Dive Action

- Dive and Adventure

- Dive Inn Cape Town

- Into the Blue

- Pisces Diving

- The Scuba School

Do

See Services directory for contact details.

Boat dive charters:

Boat dives from a specialist dive boat. Usually one dive per trip, sometimes two. Booking essential. Some operators provide a divemaster, some will rent equipment, others only provide transport. Dives may be cancelled up to the last minute if conditions turn bad. If the trip is cancelled, you can expect a refund. Some operators will cancel if they think the dive will not be good, others will launch unless it looks too dangerous. Check terms before booking.

This listing is of operators who own and run a boat. Most dive shops and schools which do not run their own boat will book boat dives for clients on these boats. This is usually the way to go if you neet to rent equipment or need transport. Direct booking is appropriate if you have your own equipment. Most dive charters will rent cylinders.

- Animal Ocean

- Blue Flash (tech friendly)

- Dive Action (tech and rebreather friendly)

- Dive and Adventure

- Indigo Scuba Diving Centre

- Learn to Dive Today

- Ocean Experiences

- Pisces Divers

- Underwater Explorers (tech friendly)

Guided shore dives:

Shore dives led by a Divemaster. Usually one dive per trip. Booking usually required. Most operators rent equipment, some provide transport to the site from a specific assembly area, usually a dive shop. Check terms before booking

- Alpha Dive Centre

- Cape RADD

- Cape Town Dive Centre

- Dive Action

- Dive Inn Cape Town

- Indigo Scuba Diving Centre

- Into the Blue

- Just Africa Scuba

- Learn to Dive Today

- Ocean Experiences

- Pisces Divers

- The Scuba School

Dive clubs:

Places where divers gather to fill cylinders, have a drink and discuss diving. Clubs also generally offer training and equipment rental to members, and air and occasionally Nitrox and Trimix fills. Only dive clubs not exclusively affiliated to a dive school or dive shop are listed here. Some clubs welcome visitors to club dive outings, but non-members will usually have to provide their own equipment.

- Aquaholics Club

- Bellville Underwater Club

- Cape Scuba Club

- False Bay Underwater Club

- Maties Underwater Club (Stellenbosch Underwater Club)

- Old Mutual Sub Aqua Club

- University of Cape Town Underwater Club

Cage Diving (sharks)

A small number of licensed operators offer open water cage diving to get up close to the great whites in their own environment. April to September is the peak time to see Great Whites in South Africa. There are morning and afternoon trips to Seal Island, where you can see the famous breaching Great White sharks of False Bay as well as cage diving, sometimes all in one trip. Not all cage diving is on scuba — in fact most is done on breathhold. Check when booking.

- African Shark Eco-Charters

- Apex Shark Expeditions

- Shark Adventures

- Shark Explorers

Fix

See Services directory for contact details.

Scuba equipment servicing and repair:

- Alpha Dive Centre

- Cape Town Dive Centre

- Dive Action

- Indigo Scuba Diving Centre

- Orca Industries.

- Pisces Divers.

Scuba cylinder inspection and testing: Most dive shops will take cylinders in for servicing by a testing facility, those listed here do the actual testing.

- Executive Safety Systems. Hydrostatic testing and visual inspections

- Orca Industries. "Visual plus" eddy current testing of Aluminium cylinders and Oxygen service cleaning on request.

Dry suit servicing and repair:

- Blue Flash.

- Stingray.

Wet suit repairs and custom fitting:

- Coral Wetsuits.

- Reef Wetsuits.

Services directory

- African Shark Eco-Charters, Shop WC13, Simon's Town Boardwalk Centre, St Georges St, Simon's Town, -34.192989°, 18.432247°, +27 21 785-1941, +27 82 674 9454 (mobile), airjaws@mweb.co.za. Office: 9AM-6PM. White shark cage dives. Great White shark cage dives R1450-1750

- Animal Ocean Marine Adventures, Mobile operation - no offices, +27 79 488-5053, animaloceandiving@gmail.com. Available any time on email or cell phone. Seal snorkelling, ocean safaris, boat charters, sardine run and specialist photographic expeditions. Local boat dive R200 excluding equipment, 2 pax minimum

- Alpha Dive Centre, 96 Main Rd, Strand (opposite the railway station), -34.11588°, 18.83079°, +27 21 854-3150, scuba@alphadivecentre.co.za. M-F 7:30AM-6PM, Sa Su 7:30AM-2PM. NAUI, PADI and DAN training; equipment sales and rental; air fills; regulator and BC servicing; boat and shore dives (Gordon's Bay).

- Apex Shark Expeditions, Quayside Building, Shop no 3, Main Rd, Simon’s Town, -34.193061°, 18.432716°, +27 21 786-5717, +27 79 051-8558 (mobile), info@apexpredators.com. White shark cage diving.

- Bellville Underwater Club, Jack Muller Park, Frans Conradie Drive, opposite DF Malan High School, -33.8905°, 18.6284°, webmaster@bellvilleunderwaterclub.co.za. Club night Wednesday, 7PM to 11PM. CMAS-ISA, and IANTD training; club dives most Sundays; air and nitrox fills for members; social club for recreational and technical divers.

- Blue Flash, 5 Glenbrae Ave, Tokai, -34.06469°, 18.44280°, +27 73 167-6677, grant@blueflash.co.za. Dry suit service, repairs and adjustments; new (Cape Gear) and used dry suit sales; recreational and technical dive charters; high-speed boat trips and marine touring; exploration of new wrecks and reefs (Cape Peninsula). Weekly e-mail newsletter can be subscribed to on the website. Local boat dive R400 excluding equipment 2018-10-04

- Cape Town Dive Centre, 122 Main Road, Glencairn Simon’s Town, 7975 Western Cape, -34.165928°, 18.431282°, +27 84 290 1157, info@capetowndivecentre.com. 9AM-4:30PM (somedays longer). PADI training and discover scuba diving experiences. For those already certified, boat launches and shore dives. Scuba equipment sales and rental, as well as equipment servicing and repairing. 2015-07-07

- Cape Scuba Club, info@capescuba.co.za. Weekly social gatherings. Cape Scuba Club is a fun, family-based scuba diving club. Members get: Discounted air fills, discounted boat charters, support from experienced scuba divers, weekend scuba diving in Cape Town led by experienced divers, including night dives, wreck dives, boat dives and shore entries, and weekend scuba diving trips.

- Coral Wetsuits, 60 Hopkins Street, Salt River, -33.93148°, 18.45683°, +27 21 447-1985, coralwet@mweb.co.za. Stock and custom wetsuits. Wetsuit tailoring and repairs.

- Dive Action, 22 Carlisle St, Paarden Eiland., -33.91561°, 18.47049°, +27 21 511-0800, info@diveaction.co.za. M-F 8:30AM-5.30PM, Sa 8:30AM-1PM. PADI and IANTD training (NAUI on request); recreational and technical dive charters (Cape Peninsula); equipment sales and rentals; air, nitrox, oxygen and trimix fills; regulator and BC servicing; re-breather fills and sorb. High-speed boat trips and tours. Local boat dive R350 excluding equipment

- Dive and Adventure, Gordon's Bay, +27 83 962-8276, diveandadventure@yahoo.com. CMAS-ISA training; equipment rental; boat dive charters (Gordon's Bay); air fills; small boat skipper training.

- DiveInn Cape Town (Carel van der Colff), -34.0249°, 18.4792°, +27 84 448-1601, carel@diveinn.co.za. Private RAID scuba dive training, Nudibranch hunter specialist, First aid course through DAN, equipment rental, private tours to Cape Winelands, Cape Town city, Cape Peninsula, boat dives, private scuba dive via shore. Shore dive including weights and air R380 2022-11-01

- Executive Safety Services (E.S.S.), 4 Dorsetshire St, Paarden Eiland, -33.91578°, 18.47039°, +27 21 510-4726, executivesafety@telkomsa.net. M-Th 8AM-4PM, F 8AM-3PM. Scuba cylinder visual inspection and hydrostatic testing; Service of pillar valves; Air fills up to 300bar.

- False Bay Underwater Club, Under Wetton road bridge, Wynberg (Entrance is in Belper road, off Kildare road), -34.00271°, 18.47324°, info@fbuc.co.za. Club night Wednesday, 7PM to 11PM. CMAS-ISA, SSI and IANTD training; club dives most Sundays; air, nitrox and trimix fills for members; social club for recreational, technical and scientific divers, Spearos and Underwater hockey.

- Indigo Scuba Diving Centre, 16 Bluegum Avenue, Gordon's Bay, -34.15688°, 18.87335°, +27 83 268-1851 (Mobile), info@indigoscuba.com. M-F 9AM-5PM, Sa Sun 8:30AM-2PM. SSI training ; equipment sales and rental; air fills, equipment servicing. boat and shore dives. Dive charters & sea safaris 2019-10-24

- Into the Blue, 88b Main Road, Sea Point (Right across from the Pick 'n Pay in Sea Point Main Road), -33.910332°, 18.394151°, +27 21 434-3358, +27 71 875-9284 (mobile), info@intotheblue.co.za. M-Sa 9AM-6PM. PADI training. Equipment rental. Shore dives 7 day per week conditions permitting. Boat dives W, Sa and Su. Shark dive bookings and transport. Transportation provided from city centre. Boat dives R280, full equipment rental R360/day

- Just Africa Scuba, Unit 17, The Old Cape Mall, 33 Beach Rd, Gordon's Bay (Corner of Sir Lowry Road. Shop is at the back of the mall.), -34.157075°, 18.868192°, +27 82 598 1884, info@justskills.co.za. M-F 8AM-6PM, Sa-Su 8AM-1PM. PADI training, shore and boat dives, Seal island boat trips Shore dives from R300 including cylinder, boat dives from R450 excluding cylinder 2019-10-04

- Learn to Dive Today, 5 Corsair Way, Sun Valley, Cape Town, -34.125545°, 18.401919°, +27 76 817-1099, tony@learntodivetoday.co.za. SDI and PADI scuba training, boat charters and guided boat and shore dives. Equipment rental for students. DAN Business member.

- Maties Underwater Club (Stellenbosch Underwater Club), University of Stellenbosch sports grounds, Coetzenburg, Stellenbosch, -33.9388°, 18.8782°. Open membership recreational diving club. Scuba, Spearfishing, Underwater Hockey; Equipment rental and air fills for members.